As part of FORSEA dialogue on Democratic Struggles across Asia Series, I recently hosted a bi-lingual in-depth discussion n Burmese and English on the subject of Balkanizing the Union of Burma – now the Union of the Republic of Myanmar. Talking about Balkanization of my country of birth reminds me of a precious little conversation I had with my late close relative in Mandalay some 30-odd years ago.

“Ko Aung San, your idea of Burma’s independence from the Mighty British is a complete pipe dream, do you not think?!,” quipped his classmate and dorm neighbour Ko Zan Yin, as the two sat and chatted in the latter’s room at Pegu Hall, in the old colonial Rangoon University in the mid-1930. Rangoon University was the only university in the country, and had just been a major site of anti-colonial activism.

Zan Yin was the younger brother of my maternal grandfather. Both Aung San and Zan Yin, were two young lads from petty bourgeoisie families from the Burmese heartlands in the Dry Zone, then known as Upper Burma. After matriculation, they came to Rangoon, the only university in colonial Burma, with their own respective personal ambitions. Like a large proportion of university students in those days, my relative was determined to become a member of the administrative ruling strata, colloquially referred to as “the heaven-born”.

Recounting his conversation with his friend Aung San, who went on to become a fully-fledged revolutionary leader and founded the Burma Independence Army as a nationalist proxy for Japan against the British in Burma, U Zan Yin proceeded to tell me of Aung San’s rather nonchalant response. “Yes, you are right, Ko Zan. The chances of my mission succeeding are very slim. But my ultimate dream is Burma’s liberation. Maybe I’ll end up on gallows instead. Who knows?!”

Subsequently, the British Crime Investigation Department in Rangoon ranked Aung San “State Enemy Number One”, which triggered the radical nationalist’s attempt to flee the colonial Burma and eventually obtained Fascist Japan’s material support, military training and political patronage, which in turn enabled the Burmese nationalists to set up their own pro-independence military against the British rule, then in its 100-years.

The decision by Aung San, a Burmese radical, to team up with the Fascists in Tokyo has since been typically condemned by the British and the western-educated Burmese liberals for the nationalists prepared to do anything – including walking gallows for freedom from economically predatory and racist colonial British rule. The Brits, liberal and conservative alike, were scornful of the choices that pro-independence Burmese radicals made in the inter-war years of the 1930’s and early 1940’s – like embrace of Communism or pragmatic ally ship with Japanese Fascists.

To the Burmese, emphatically speaking, Fascism and Colonialism differed, in essence, only in degree, not in kind. After all Fascists such as Hitler drew their inspiration from Colonialism and colonial empires, established by Western European powers, specifically Britain.

And my relative did join the Burma Civil Service (BCS) and retired as Commissioner of Saggaing Division, the ancient region across the Irrawaddy from my home city of Mandalay, where the fighting between civilian resistance forces and the Myanmar military are raging on over the last several months.

As with Aung San, ten years on from those neighbourly conversations of Pegu Hall in the 1930’s, the Burmese nationalist student realized his dream of an independent Burma. And he did not end up on the colonial gallows, but was assassinated by his local nationalist rival, assisted by the British elements in Burma on the eve of the country’s independence.

And the rest is history as they say.

Back to the FORSEA Dialogue on Balkanizing Myanmar in 2021.

My guest on the dialogue was Mr Rual Lian Thang (nicknamed Boi Boi), a youngish, articulate, and thoughtful Chin scholar and activist. Educated at the Central European University in Budapest and subsequently at the Australian National University, Boi Boi carefully chose his words, both in Burmese and English sessions, as he explained perspectives on the failed post-independence Union of Myanmar in the grip of the Fascist-like military.

Like all other crucial issues in Myanmar affairs, the genocide of the Rohingya, the charade of the military-led “democratic reforms”, the failed leadership of iconic Aung San Suu Kyi, or the complicity of the United Nations in the emergence of Myanmar as “failed state”, any mention of Balkanization will typically be met with scornful incredulity, if not outright rejection in international policy circles as well as among the anti-junta resistance groups.

While a student in Budapest, he travelled the Balkans, former sites of Yugoslavia’s break-up, and saw the parallel between post-Tito Yugoslavia and post-Aung San Union of Burma or Myanmar. In the case of Yugoslavia, 6 different ethnic nations with their own sovereign republics or polities, forged under the Croat Tito as a confederation, to be protected by the sizeable military made up of majority Serb. Some republics were born out of the dissolution of the old Ottoman Empire only around the turn of the 20th century. In Myanmar’s case, half-dozen ethnic nations, with their own sovereign political systems, historical memories, mutually incomprehensible linguistic cultures and political aspirations voluntarily joined together to form a post-colonial Union, a federation with equal group rights, including the right to self-determination and group equality, not simply liberal individual rights of human persons (or human rights).

Alas, the creation of new sovereign republics out of the failed Union of the Republic of Myanmar is the modern-day equivalent of Aung San’s “liberation from the British rule”.

It is typically dismissed as “a pipedream”. None of the neighbouring counties with their own domestic minority rebellions – China, India, and Thailand, in particular – would welcome the Balkanized Myanmar as a contemporary source of neighbourhood inspiration for their repressed minorities. That is in addition to the further instability in Myanmar and the cross-border spill-over impact from such a centrifugal process.

These are external impediments. And my guest was painfully aware of these facts.

The fact that the Union of Myanmar under the Burmese military has failed is not in dispute. And a radically different type of confederation of ethnic nations with group equality – not just liberal individual human rights – is a common aspiration among different groups.

Even the many well-armed, capable Ethnic Armed Organizations such as the Kachin Independence Army, the Karen National Liberation Army and the Arakan Army with the common pro-self-determination stances know only too well that surrounded by illiberal regimes within and without Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Myanmar’s prospects for Balkanization do not have NATO to help.

Quite the contrary, whatever their pro-human rights and pro-democracy rhetoric, the Asian neighbours operate with the tacit view that Myanmar’s terrorist military will in due course prevail. As one Singaporean academic recently put it, “they (Myanmar military) can fight (and survive) for another forty years”.

Never mind that this national military been committing all grave crimes in international law, including a textbook genocide against Rohingya, war crimes and crimes against humanity against the rest of the society, including ethnic minorities and Buddhist Bama majority.

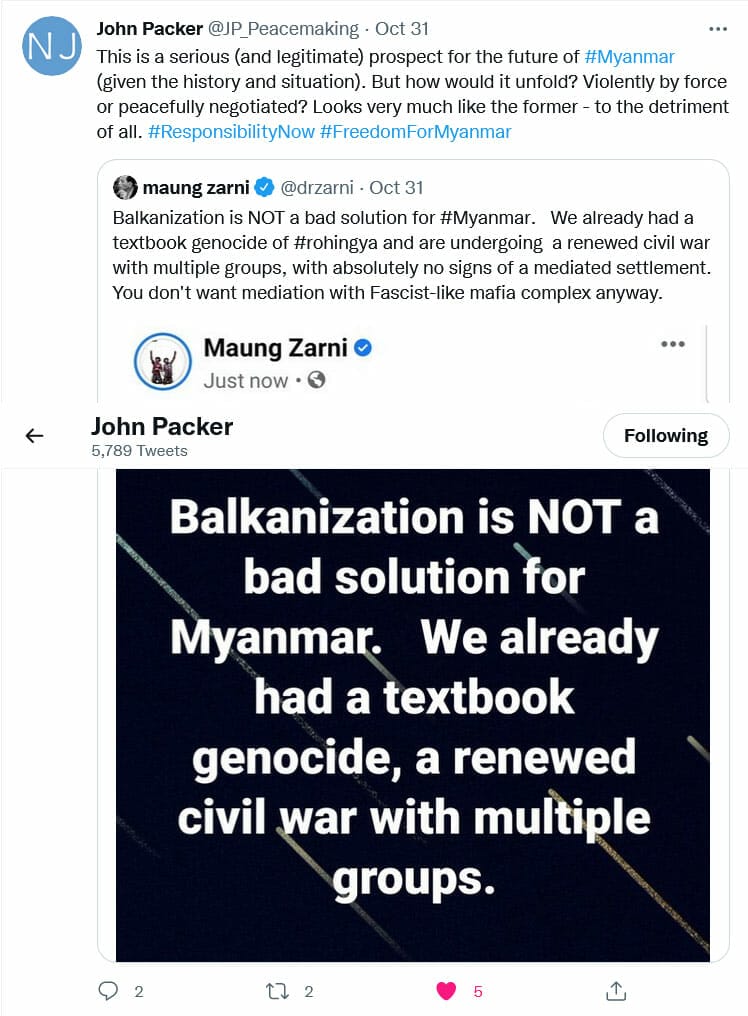

On 31 October, John Packer, the University of Ottawa law professor in international conflict resolution, chimed in with a tweet: “This (Myanmar Balkanizing) is a serious (and legitimate) prospect for the future of #Myanmar (given the history and situation). But how would it unfold? Violently by force or peacefully negotiated? Looks very much like the former – to the detriment of all. #ResponsibilityNow #FreedomForMyanmar”.

The greatest irony in the increasingly mentionable word “Balkanization” is this:

The greatest irony in the increasingly mentionable word “Balkanization” is this:

No organization in Myanmar has been more concerned about the Union of #Myanmar “Balkanizing” than the terrorist military, and yet its behaviour has triggered the slow, if unacknowledged process of Myanmar’s disintegration.

After all Aung San’s pipe dream of liberation from the Mighty British Empire proved a realizable goal, as soon as the external geo-political equation shifted markedly and irreversibly with the arrival of the WWII.

Listen to a conversation with Demir Mahmutcehajic, a prominent Bosniak human rights activist on the FRC Genocide Podcast Series –

As a matter of fact, Myanmar military strategists and propagandists have almost nearly doubled the number of ethnic groups which may qualify the label “ethnicity”, less than 80 by the counts in the 1960’s and 1970’s, to “135 national races”, indigenous to Myanmar. Very recently, on YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=meBl2gYlwjM , the audio-recording of a public event from 1963 surfaced, during which one of the most respected folklorists and journalists the late Ludu U Hla, revealed that his own studies indicated that the Burma during the Revolutionary Council rule of General Ne Win had less than 80 ethnic groups.

Slightly fewer figures – around 70 ethnicities – were recorded by the late Rakhine historian Dr Aye Kyaw and Ne Win’s Secretary of Education Dr Nyi Nyi in their respective tallies of ethnic groups in Myanmar, in the 1970’s.

My guest Boi Boi (Rual Lian Thang), a Chin from Thangtalang city where several hundred residential homes were deliberately torched by Myanmar military troops, pointed out that large extended families and clans with slight variations in dialect, among the Chin peoples in Western Myanmar are counted as separate “national races!

Their strategic rationale behind vastly inflating the number of ethnic groups is to create and justify the self-serving perception of Myanmar as a highly diverse country that needs a strong hand of the military, for stability and territorial integrity.

No Burmese would want further political instability or loss of territorial integrity of their country. But when that strong hand is choking off the entire multi-ethnic public in the name of “preserving the Union” the Balkanization is most certainly an objective worthy of pursuit, however long the process.

As a Karen intellectual Saw Kapi urges us, “let’s look at this (Balkanization) as a political labour during which new republics are given birth to.”

What’s so bad about liberations of the Wretched of the failed Fascist union of Myanmar?

In passing, as a Burmese from the Dry Zone heartlands of Myanmar whose friends and family in the armed forces known as the Tatmadaw spent their life defending the Union – some gave up their lives and limbs – I want to spell out clearly my stance on this taboo subject: I see the Balkanization of Myanmar as the only viable end to what the overwhelming majority of Burmese public, including religious and ethnic minorities, experience as a home-grown Fascist occupier. To us, not only has the original Union of Burma failed but it has morphed into the people’s worst nightmare: a Fascist state with economically predatory mafia features.

Maung Zarni

Banner image: Gayatri Malhotra Unsplash